The evidence: low traffic neighbourhoods

Much has been written recently about low traffic neighbourhoods and how they do or don't benefit our local communities. A large amount of this has been based on anecdotal evidence and people's opinions. But what do objective evidence and credible studies show?

Is there even a problem?

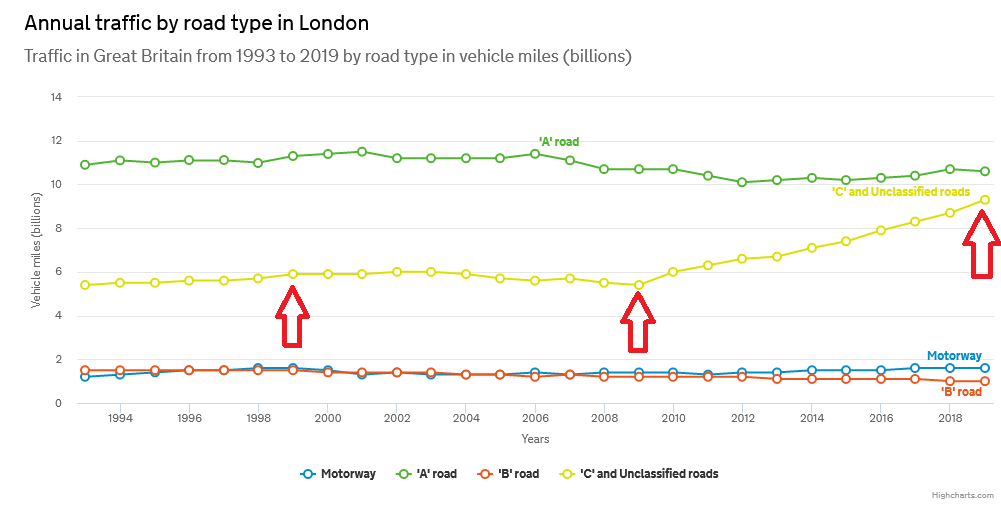

Our side roads have always been open; indeed, “knowing the shortcuts” has been a much-vaunted skill, so why the sudden need to close-off these roads? The reason is the huge increase in traffic now using these roads, due largely to the use of satellite navigation apps such as Waze and Google maps. The graph below shows (in yellow) the increase in vehicle miles on residentials streets, whilst the traffic on main roads has actually decreased slightly.

Over the same period, walking and cycling casualties on neighbourhood roads have shot up, as shown by TfL’s latest analysis of STATS19 data. Neighbourhood streets are not designed to carry lots of traffic. They have blind corners, few crossings and more people are out and about. A driver cutting through a side street is much more likely to injure or kill than a driver on a main road. A recent study found that:

On urban roads, driving a mile on a minor urban road is twice as likely to kill or seriously injure a child pedestrian, and three times more likely to kill or seriously injure a child cyclist, compared to driving a mile on an urban A road.

So now that we've identified the problem, what benefits do low traffic neighbourhoods bring?

Low traffic neighbourhoods reduce road danger

New research into Waltham Forest LTNs compares police injury data (STATS19) inside the LTNs with other areas and with the same streets before implementation in 2015-2016. This suggests that walking, cycling and driving within an LTN all become 3-4 times safer per trip, with no change in road danger on the boundary roads. Read the report: The Impact of Introducing Low Traffic Neighbourhoods on Road Traffic Injuries.

Low traffic neighbourhoods allow more people to cycle

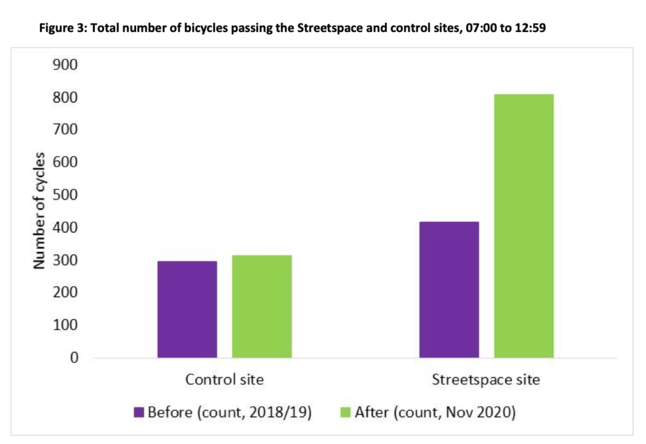

Conducted by residents but with guidance and methodology from Dr Anna Goodman, this work compared the number of people on bikes with pre-intervention ‘manual’ counts by the Department for Transport.

They found impressive increases in the numbers cycling, especially among children, and the report concluded:

“the large increase in cycling at the Streetspace site demonstrates the substantial potential to increase cycling if infrastructure is provided that allows people to travel safely and comfortably…installing modal filters is a very effective way to make this happen”.

Low traffic neighbourhoods reduce car ownership

This isn't about preventing car ownership: no low traffic neighbourhood scheme prevents the ownership of a car. This is about people choosing the best option for them: if the local environment is such that owning a car is no longer necessary, then why incur the expense of doing so?

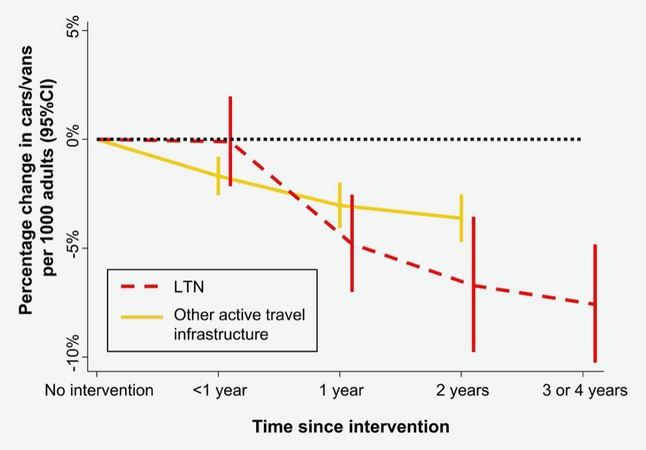

A study of London’s ‘Mini Hollands’ used vehicle registration data to examine whether active travel interventions in Waltham Forest between 2015 and 2019 affected motor vehicle ownership, compared to other neighbourhoods.

The chart shows they found statistically significant reductions in car/van ownership in areas introducing low traffic neighbourhoods: 6% less, or 23 cars/vans per 1000 adults, after two years. They also found statistically significant but smaller reductions in areas introducing other infrastructure such as cycle tracks: 2% less, or 7 cars/vans per 1000 adults, after 2 years.

One of the authors said:

This is such an impressive effect. In our evaluation studies we quite often see increases in active travel, less often a mode shift away from cars. An effect of this size is unprecedented in my own sustainable transport research. It is also striking that, although LTNs show the largest effect, non-trivial reductions in car/van ownership are seen in areas that got other active travel infrastructure like cycle tracks

Low traffic neighbourhoods are not socially unjust

There have been claims that LTNs only benefit the well-off, pushing traffic from affluent neighbourhoods onto the main roads where lower-income residents are more likely to live. This study therefore looked at equity in the rollout of LTNs. Notably it found that:

“Across all groups we compared, around nine in ten Londoners live on residential streets…Differences between residential street and main road/high street residents by age group, income group, ethnic group, and disability status are relatively small, and relate more to Outer than to Inner London. Therefore implementing LTNs in itself is not likely to pose major social equity issues (by benefiting those living on residential streets more than those living on main roads).”

It also found that LTNs make little difference to traffic levels on bordering main roads: “Encouragingly, a look at traffic levels around an early LTN implementation in Walthamstow Village also suggests that traffic trends on the nearby boundary roads were little different to broader London trends.”

However, they also call for interventions to improve main roads for the sake of the 5-10% of the population who live on them.

Low traffic neighbourhoods do not hinder emergency vehicles

Another study of Waltham Forest focuses on emergency vehicle response times. There’s a natural focus on Waltham Forest among these studies – simply because there is nowhere else that’s got such a wide area covered by interventions that have had time to bed in, so that studies can take place over a meaningful period. The report summary says:

“There is sometimes concern that low traffic neighbourhoods slow emergency vehicles. We test this using London Fire Brigade data (2012-2020) in Waltham Forest, where from 2015 low traffic neighbourhoods have been implemented. We find no evidence that response times were affected inside low traffic neighbourhoods, and some evidence that they improved on boundary roads. However, while the proportion of delays was unchanged, the reasons given for delays initially showed some shift from ‘no specific delay cause identified’ to ‘traffic calming measures’. Our findings indicate that low traffic neighbourhoods do not adversely affect emergency response times, although while LTNs are novel this perception may exist among some crews.”

That last point is interesting – emergency service vehicles are held up by traffic congestion, and poorly parked vehicles, all the time. The problem is always too many motor vehicles but now every momentary hold up is blamed on low traffic neighbourhoods, frequently when there have not even been any local changes to the road network.

Low traffic neighbourhoods do not significantly impact periphery roads

We've all seen photos of queues of cars and claims of “gridlocked” roads as a result of low traffic neighbourhoods. But congestion on London's roads is not a new phenomenum and it's easy to make such claims. So what does the evidence and empirical data show us?

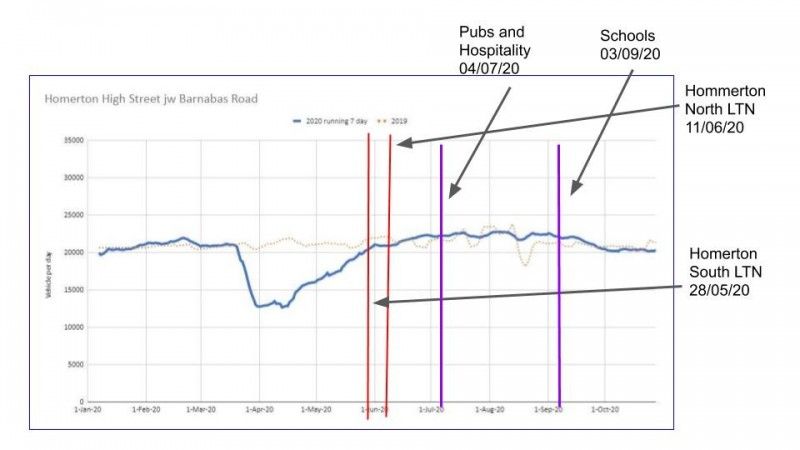

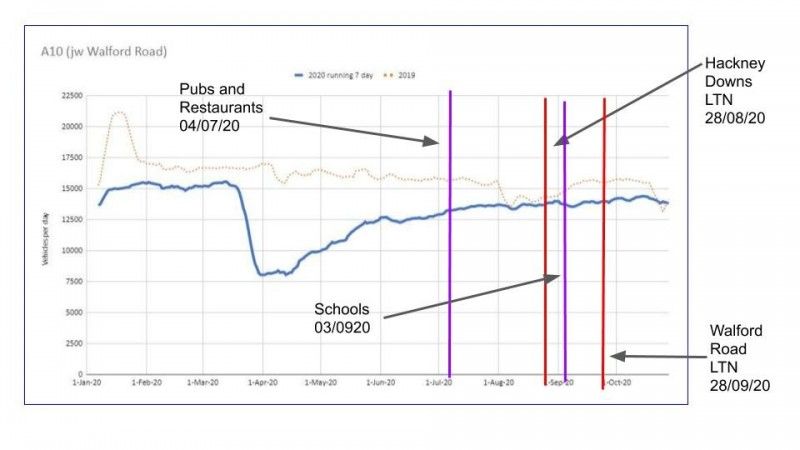

Although early days, traffic counts on Hackney's roads have shown no discernable difference since low traffic neighbourhoods were introduced there. The analysis used data from five TfL traffic count monitoring sites on roads adjacent to low traffic neighbourhoods in the borough. 2 sample graphs of the traffic levels are shown below (the faint dashed line shows 2019 data from the same period).